Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI)

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) at a glance:

- Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) is the technique of injecting a sperm directly into an egg to promote fertilization.

- ICSI, which is utilized as part of in vitro fertilization (IVF), has revolutionized the treatment of male factor infertility by helping men whose sperm are unable to penetrate the egg for fertilization.

- According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), ICSI typically fertilizes 50-80 percent of eggs, and at TRM we experience a 70 percent ICSI success rate.

- Overall fertilization rates and pregnancy rates with ICSI are slightly better than with the conventional insemination technique used in IVF.

- ICSI adds cost to fertility treatment expense and comes with a small increased risk of birth defects, so it is typically reserved for certain situations including sperm quality/quantity issues, previous failed IVF, unexplained infertility and for patients utilizing preimplantation genetic testing (PGT).

What is intracytoplasmic sperm injection?

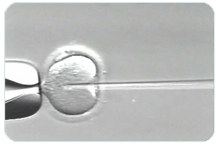

ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) is an assisted reproductive technology and part of IVF that injects a single sperm through an egg’s outer surface and into the cytoplasm where fertilization occurs. In normal reproduction and in traditional insemination during IVF, the sperm must first attach to the egg’s outer surface (the zona pellucida) and then break through into the cytoplasm.

ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) is an assisted reproductive technology and part of IVF that injects a single sperm through an egg’s outer surface and into the cytoplasm where fertilization occurs. In normal reproduction and in traditional insemination during IVF, the sperm must first attach to the egg’s outer surface (the zona pellucida) and then break through into the cytoplasm.

Egg fertilization is a fundamental aspect of reproduction and is hampered most often by poor sperm quality, but also by an unusually thick zona pellucida. In traditional IVF insemination, many sperm (possibly 50,000 +) are placed around a retrieved egg in a laboratory dish. By putting the sperm in position around the shell of the egg to fertilize the egg, this aspect of IVF substitutes for the natural process of sperm finding an egg in the woman’s fallopian tube. But the sperm must still do the work of attaching and breaking into the egg’s cytoplasm for fertilization, and this is where problems can arise.

Sam and Alicia needed all the help they could get to get pregnant.

Who may need ICSI?

ICSI may help resolve male factor infertility issues for any man who has an abnormal semen analysis. For those reasons (listed below) and due to other female issues, the following situations may call for ICSI:

- Low sperm counts

- Low sperm motility (ability to move effectively)

- Abnormally shaped sperm

- The man does not ejaculate sperm (azoospermia) and it must be retrieved surgically*

- Eggs with a thick zona pellucida

- Few eggs are retrieved in IVF

- Previous failed or low fertilization with IVF

- Unexplained infertility with no history of prior fertilization.

*Azoospermia generally indicates that a low quality of sperm would be retrieved surgically, so these men may need to consider using donor sperm.

Many couples choose to utilize ICSI even when they have none of the issues above because it can increase the chance of fertilization success. Even though ICSI adds cost to the overall IVF procedure, if it results in success then another round of IVF and its costs may be avoided. About 89 percent of our IVF procedures involve ICSI. According ASRM, ICSI fertilizes 50%-80% of eggs.

An important factor to consider in deciding whether to use ICSI is the individual fertility lab’s success rates. At TRM our ICSI fertilization rates are higher than standard fertilization rates (70 percent with ICSI and 52 percent with standard).

How ICSI is performed

ICSI is generally performed on as many eggs as possible. But ICSI can only be done using readily identifiable mature eggs. Immature eggs are discarded, as they are not capable of fertilization.

It is also possible to perform ICSI on some retrieved eggs and to attempt standard insemination and natural fertilization on the other retrieved eggs. This is sometimes referred to as half ICSI or split ICSI. An individual’s or couple’s fertility physician will discuss the pros and cons of this approach.

Prior to the procedure, an embryologist evaluates a semen sample for quantity and quality in a fluid medium. The ICSI process takes place in a special high-powered microscope station. The steps in the process are as follows:

- The embryologist at the microscope station holds the mature egg in place with an instrument

- The embryologist uses a micropipette (small, hollow needle) to draw in a single sperm swimming in the prepared medium

- He or she then locates the appropriate place on the egg’s outer layer and injects the sperm through the layer and into the cytoplasm

- The needle is carefully removed so as not to damage the egg

- These steps are repeated for each egg that is to be fertilized

- The eggs are monitored the following day for evidence of fertilization

- The fertilized egg(s) (now embryos) grow in the lab for three to five days and are either implanted into the woman’s uterus with the hope that pregnancy will occur, or undergo biopsy to test for genetic abnormalities prior to embryo transfer

- Any remaining embryos can be frozen for future use in IVF, donated to another couple, donated to scientific research or destroyed.

There is always a chance that embryos will not form, or if they do that pregnancy will not occur or be sustained. Once fertilization via ICSI does take place, the chance of a successful birth are the same as with any IVF fertilization.

Risks of using ICSI

A direct risk of ICSI is that the procedure may damage some or even all of the eggs injected with sperm. Some studies have shown that the chance of a birth defect in a child conceived via ICSI is slightly higher than the chance of a birth defect from standard IVF births. But it is unclear from existing studies whether it is the technology itself or the underlying reason for why the couple needs ICSI that is associated with the higher rate.

Some conditions are associated with ICSI, including abnormalities of sex chromosomes, Angelman syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and hypospadias. According to ASRM, these are thought to occur in much less than 1 percent of ICSI births.

Regardless, the risk is still very low and just slightly above the birth defect rate associated with a spontaneously conceived birth, which is 1.5-3 percent. It is important to remember that on balance, the risks of not using ICSI in IVF cycles usually outweighs the risks of ICSI. In appropriate cases, failure to use ICSI can cause low fertilization or failed fertilization and subsequent low or no available embryos, which is a far more likely outcome than the low incidence of birth defects.